Why do we have patents?

Innovation takes a variety of forms, and patents are just one of several tools that policymakers use to encourage innovation. Let’s look at the alternatives to better understand why patents exist.

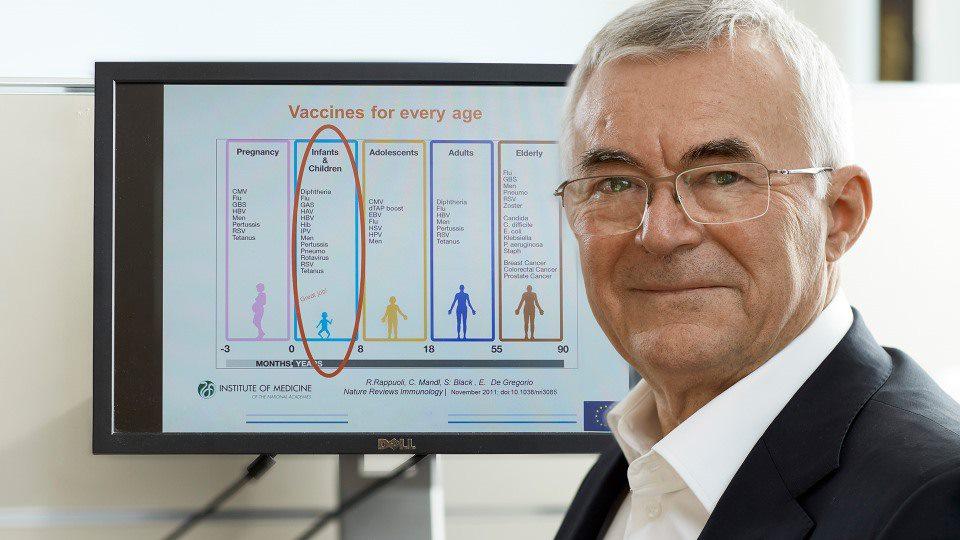

whooping cough and other infections

Some of the greatest inventions or spurs to innovation have been competitions. The first spring-driven clock was the result of a prize offered 300 years ago by the British Admiralty, which was looking for reliable ways to keep time on ships. Big cash prizes were offered as incentives to the earliest aviators to chase the dream of powered flight, and motorsport prizes still drive automotive technology that trickles down into regular cars. Such incentives sometimes work, but sometimes fail. A “winning” invention might meet the criteria of a competition, but still not be a market success.

Similarly, governments give out money to researchers and engineers in the form of grants, loans or tax breaks on research and development investment. This too encourages inventive activity, but still does not guarantee that the end result would be commercially viable.

Companies can instead innovate purely for their own profit and to get a competitive edge over their competitors. Competitors will only want to copy their innovation if it gains them market share. However herein lies another problem. If a new technology is expensive to develop, yet easy to copy and hard to protect, there is no incentive to innovate. Conversely, if low barriers to copying are no problem for companies to try out new things (known as “first mover advantage”), then policymakers see no need to interfere in the market by adding patents. This explains why they exclude pure “business methods” from patent protection.

optical coherence tomography (OCT)

Some companies use trade secrets to protect their unique technology. If the technology concerns a process rather than a product, they can keep this secret for years. Centuries ago, secrecy was the only way to enjoy a competitive advantage for new inventions. The medieval craft guilds jealously guarded manufacturing techniques, recipes and sources of rare raw materials; any member revealing these secrets risked expulsion from their guild. The problem was that an artisan's emigration or death could lead to the loss of irreplaceable knowledge!

For this reason the Senate of Venice asked its skilled glassmakers to share their knowledge by training apprentices, rather than take their secrets abroad or to the grave. The glassmakers were understandably reluctant because they feared competition from the younger generation. So the Senate offered them protection from competition for a limited period in exchange for the sharing of their knowledge.

This marked the birth of the patent system as we know it today. Inventors published their technical secrets in return for a short-lived exclusive right to their new technology.

In sum, the patent system incentivises innovation in three ways that none of the alternatives can match. It promotes:

-

Knowledge-sharing: Our public patent database, Espacenet, contains over 150 million patent documents from over 100 countries. All this information is free and can be used as a springboard for new inventions. The database doesn’t just contain granted patents, but all patent applications too. In other words, it gives access to every idea anyone has ever had and tried to get a patent for, whether or not they were successful.

-

R&D investment: The promise by the state to defend inventors’ rights (by providing courts and a legal framework) gives innovators the confidence to fund research and development. As a result, innovators can attract investment, earn licensing revenue and secure market share.

-

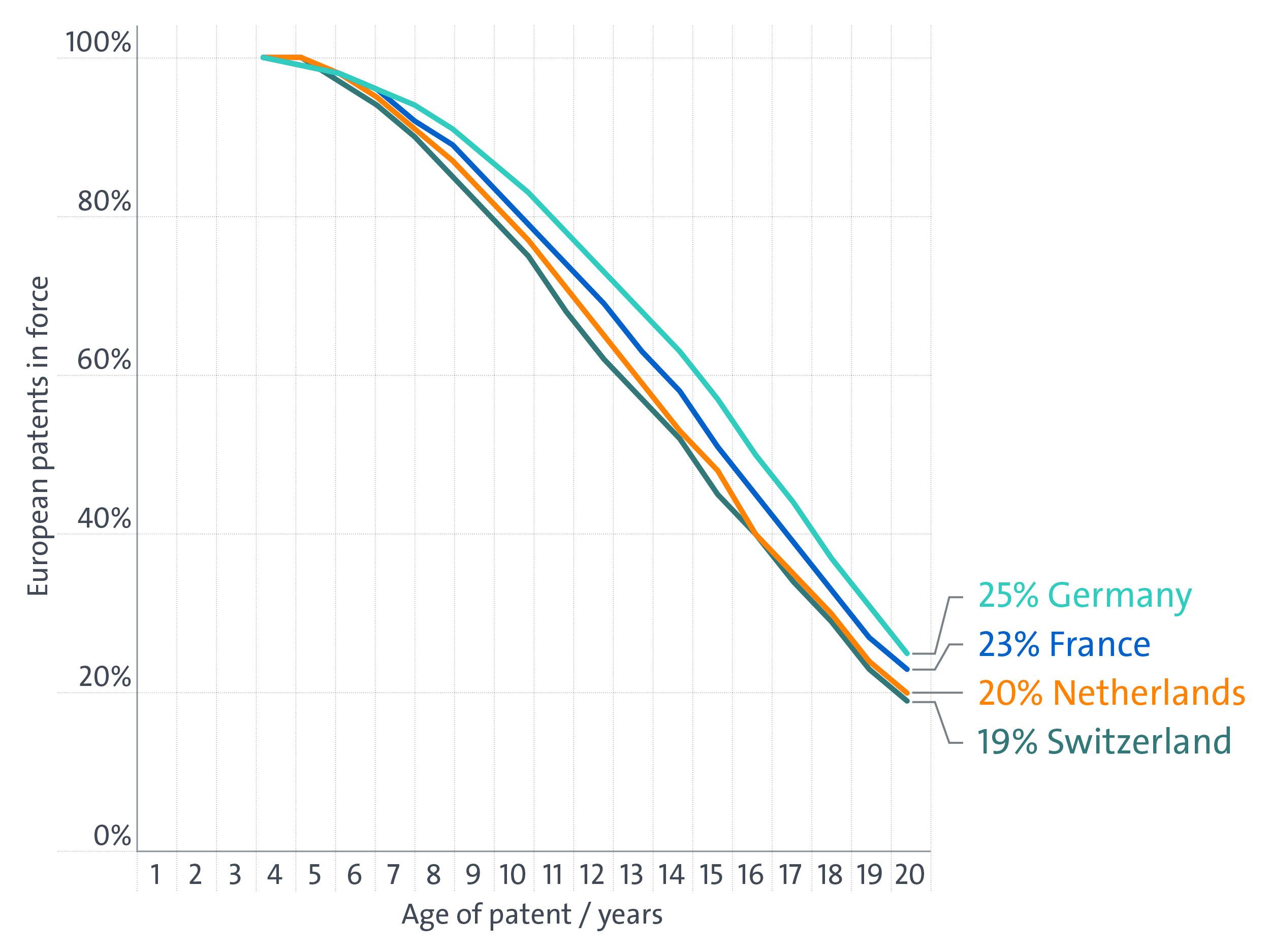

Technical advances that really matter: The requirement to pay annual renewal fees – which get costlier each year – means that patents are maintained only on those technologies which are valued by the market and still generate value. Patents on redundant technologies lapse, and the technology becomes free for anyone to use. Only a minority of patents are renewed until their 20th and final year. And because patents ultimately expire and cannot be renewed forever, even their inventor cannot be complacent and must continue to innovate.

Renewal fees have an additional role in the patent system: the revenues offset front-end costs. The European Patent Office does not pass on the full cost of patent search and examination to applicants through its fees, so as to keep costs down for inventions in their early stages. But revenues from renewal fees for the most successful inventions cover this gap, pay all the EPO’s staff costs and overheads, and effectively subsidise the patent application system for everyone. In other words, those already benefitting the most from the patent system partially cover the patenting costs for the next generation of inventions.